Perhaps in lieu of (or, as it may turn out, in addition to) his customary letter for Advent, Bishop Gerard de Korte has written a letter about the upcoming Holy Year of Mercy to the faithful of his diocese. In it, he writes about the importance of mercy as it is a fundamental element of the identity of God. He identifies two kinds of mercy – moral and social, and further divides the latter in three constituent elements or expressions: in our own lives, in the Church and in society. He concludes his letter by underlining the message of Pope Francis, as expressed in his encyclical Laudato Si’: that, by living mercy in these three contexts, we should work with others to build a society of mercy.

Read my translation below:

“Brothers and sisters,

On 8 December, a Marian feast and also the date of the end of the Second Vatican Council fifty years ago, the Year of Mercy will begin in our Church. It is an invitation to look critically at how our parishes function, but also at our own existence. How merciful and mild do we treat one another? Do we mostly see what’s alien and strange in the other and do we mindlessly ignore the good? Do I give someone who has done wrong a new chance? Am I really willing to help when someone is in need?

Shortly after his election as bishop of Rome, Pope Francis gave an interview that was published in a number of magazines of the Jesuit Order. The Pope called himself a sinner called by the Lord. He referred to a painting by Caravaggio, depicting the calling of Matthew. Apparently our Pope recognises himself strongly in Matthew. As a tax collector, a despised collaborator of the Roman occupiers, he is invited to experience forgiveness and a new start. Christ meets him with merciful love and calls him to follow Him. Pope Francis lives from this some merciful love of Christ.

Office holders in the Church are especially invited to take a look in the mirror. Pope Francis recently quoted from an address by Church father Ambrose: “Where there is mercy, there is Christ; where there is rigidity, there are only officials”. This is an incisive word which everyone with a pastoral assignment in our faith community must consider seriously. In this context I would like to refer to the book Patience with God by the Czech priest Tomas Halik. A great number of people, within and without our Church, are like Zacchaeus in the tree from the Gospel. They are curious but also like to keep a distance. To get in touch with them requires pastoral prudence and mildness on the part of our officials.

In this letter I would like to zoom in on the word mercy, which for many of our contemporaries is probably somewhat old-fashioned and outdated. What is mercy actually? Maybe the Latin word for mercy, misericordia, can help us. A person with misericordia has a heart (‘cor‘) for people in distress (‘miseri‘): sinner, the poor, the grieving, the sink and lonely people. The Hebrew word for mercy is not so much concerned with the heart, but with the intestines. A person with mercy is touched to the depths of his belly by the needs of the other.

God is a merciful God

In Holy Scripture we often hear about the mercy of God. Even until today the Exodus, the departure from slavery in Egypt and the arrival in the promised land, is for the Jewish people a central topic of faith.

God has seen the misery of His people in Egypt and had compassion with His people (Exodus 3). Elsewhere in the book of Exodus we read, “God of tenderness and compassion, slow to anger, rich in faithful love and constancy” (cf. Exodus 34,6). For Israel the Lord is supportive mercy, making life possible.

The history of ancient Israel is a history of loyalty and infidelity. The decline of the Northern Kingdom in the 8th century and of Judah and Jerusalem in the 6th century BC has been interpreted by the Jewish people as punishment for sins. The people as bride have been unfaithful to the divine bridegroom. But punishment is never God’s final word. The prophet Hosea writes that God does not come in anger (cf. Hosea 11). In God, mercy is victorious over His justice[*]. Ultimately there is forgiveness and a merciful approach.

In the letter in which he announces the Year of Mercy, Pope Francis calls Christ the face of God’s mercy (‘misericordiae vultus‘). In Him God’s great love for man (‘humanitas dei‘) (Titus 3:4) has become visible. The great Protestant theologian Oepke Noordmans published a beautiful collection in 1946, with the title “Sinner and beggar”. In it, Noordmans touches upon the two most important dimensions of God’s mercy. Not only moral mercy but also social mercy. In Christ, God is full of merciful love for both sinners and beggars.

Moral and social mercy

God’s moral mercy is depicted most impressively, as far as I can see, in the parable of the Prodigal Son. A son demands his inheritance from his father, who yet lives, and wastes the money on all sorts of things that God has forbidden, In the end he literally ends up among the pigs. To Jewish ears this is even more dramatic than to us, since in Judaism pigs are, after all, unclean animals. In this situation, there occurs a reversal. The son memorises a confession of guilt and returns to his father. In the parable we read that the father is already looking for his son and, even before the confession has been spoken, he embraces him. Here we find what Saint Paul calls the justification of the Godless man. God is as “foolish” as the father in the parable. It is the foolishness of merciful love. God is inexhaustible love and gives his son a new chance, even when he has turned away from Him (cf. Luke 5:11 etc).

Social mercy is depicted sublimely in the parable on the Good Samaritan. A man is attacked by robbers and lies on the side of the road, half dead. Several people from the temple pass by, but they do not help. Then a stranger passes, a Samaritan who many Jews look upon with a certain amount of negative feelings. But this distrusted person acts. He becomes a neighbour to the person lying on the side of the road. He treats his wounds and lets him recover in an inn, on his costs. The Church fathers, theologians from the early Church, have seen Christ himself in the person of the Samaritan. He comes with His merciful love to everyone lying at the side of the road of life. Christ has gone the way of mercy until the end. He lives for His Father and His neighbour until the cross. In this way, Christ shows that He has a heart for people in misery: the poor, sinners, people dedicated to death (cf. Luke 10:25 etc).

Is God merciful to all?

We are all temporary people. None of us here on earth has eternal life. Sooner or later death will come and take life away. In that context we could wonder what we can hope for. Are we like rockets burning up in space or can we look forward to returning home? Over the course of Church history this has been discussed both carefully and generously. Not the most insignificant theologians, such as Augustine and Thomas Aquinas, were in the more careful camp, with the Scripture passage in mind which says that “many are called, but few are chosen”. There was also another sound in the early Church. The theologian Origen was so filled with God’s love that he could not imagine that anyone could be lost. The Church, however, based on the witness of Scripture, has denied this vision. There are too many passages in Holy Scripture which leave open the possibility of being definitively lost.

In our time, however, our Church is generally optimistic regarding salvation. God’s desire to save does not exclude, but include human freedom. God’s hand is and remains extended to all. Only God knows who takes this hand. Not without reason do we pray, in one of our Eucharistic prayer, for those “whose faith only You have known.” God’s mercy maintains its primacy. Christ has, after all, died for all men. God is loyal and the cross and resurrection of Christ can be a source of hope for us all. In other words: God takes our responsibility seriously, but I hope that He takes His love even more seriously.

Culture of mercy

God’s mercy requires a human answer, a culture of mercy. Here we can discern at least three dimensions: personal, ecclesiastical and social. In our personal life we are called to love God and our neighbour. But we know that cracks continue to develop in relationships. People insult and hurt each other. The Gospel then calls us to forgiveness. Scripture even suggests we should postpone our worship when there are fractures in how we relate to our fellows (cf. Matthew 5:24). Forgiveness can always be unilateral. But both parties involved in a conflict are necessary for reconciliation. Christ does not only ask us for merciful love for our loved ones, but also for our enemies. We realise that this can only be realised in the power of God’s Spirit, and even then often by trial and error.

Merciful faith community

In one of our prefaces the Church is called the mirror of God’s kindness. In our time we notice a crisis in the Church. Many contemporaries have become individualists because of higher education and prosperity. This individualism also has an effect in the attitude towards the Church. Many people do believe, but in an individualistic way and think they do not need the faith community. Added to that is the fact that the Church suffers from a negative image. More thana few see the Church as institute that restricts freedom. Many think that the Church demands much and allows nothing.

As people of the Church we should not immediately get defensive. Criticism on our faith community invites us to critical reflection of ourselves. Do we really live the truth in love? Do we really care for and serve each other? A Christian community will not restrict people but promote their development into free children of God (cf. Romans 8:21).

We can see the Eucharist as the ultimate sacrament of God’s merciful love. Time and again the outpouring love of Christ is actualised and made present in the Eucharist. About Communion, Pope Francis has said words which are cause to think. According to him, Communion is not a reward for the a holy life, but a medicine to heal wounded people. The mercy of the Church also becomes visible in the sacrament of penance and reconciliation, or confession. For many reasons this sacrament has almost been forgotten in our country. At the same time I hear that in some parishes especially young people are rediscovering this sacrament. I hope that the Year of Mercy can make a contribution to a further rediscovery of the sacrament of God’s merciful love for people who fail.

Ecclesiastical mercy is of course also visible in all form of charity. Everywhere where Christians visit sick and prisoners, help people who are hungry or thirsty, cloth the naked or take in strangers, the ‘works of mercy’ become visible (cf. Matthew 25:31 etc).

Merciful society

After the Second World War Catholics took part in the rebuilding of a solid welfare state. After the crisis years of the 1930s and the horrors of the war, there was a broad desire among our people for the realisation of a security of existence. Catholic social thought, with the core notions of human dignity, solidarity, public good and subsidiarity, has inspired many in our Church to get to work enthusiastically. After all, although the Church is not of the world, it is for the world.

But in our days there is much talk of converting the welfare state into a participation state. Of course it is important that people are stimulated optimally to contribute to the building of society. But at the same time government should maintain special attention for the needs of the margins of society. Not without reason does Christian social thought call government a “shield for the weak”.

In June Pope Francis published his encyclical Laudato Si’. Here, the Pope ask attention for our earth as our common home. Catholics are asked to cooperate with other Christians, people of other faiths and all “people of good will”. The Pope urges us to join our religious and ethical forces to realise a more just and sustainable world. With a reference to St. Francis’ Canticle of the Sun our Pope pleads for a new ecological spirituality in which our connection with the Creator not only leads to a mild and merciful relation with our fellow men, but also with other creatures.

In closing

We all live from the inexhaustible merciful love of our God, as has become visible in Jesus Christ. Let us in our turn, in the power of God’s Spirit, give form to this love in our relationships with each other, in our faith communities and in our society. In this way we can make an important contribution to the building of a “culture of mercy”.

Groningen, 22 November 2015

Solemnity of Christ, King of the Universe

+ Msgr. Dr. Gerard De Korte

Bishop of Groningen-Leeuwarden”

*As an aside, not to distract from the overall message of the bishop’s letter: I am sorry to see this line here in such a way, as if there is a conflict between mercy and justice, in which one should be victorious over the other. Mercy without justice is no mercy at all, as it is deceitful. How can be kind and merciful to others if we keep the truth from them? The truth and its consequences must be acknowledged and accepted in mercy, so that we can help others living in that truth, even if they sometimes fail (as we eventually all do).

Following his earlier comments on the latest revelations about past abuse in the Catholic Church, and in light of the impact this has had on Catholics, also in the Netherlands, Bishop Gerard de Korte has written a letter to the faithful of his diocese. But its message is just as pertinent for Catholics in other dioceses and even other countries.

Following his earlier comments on the latest revelations about past abuse in the Catholic Church, and in light of the impact this has had on Catholics, also in the Netherlands, Bishop Gerard de Korte has written a letter to the faithful of his diocese. But its message is just as pertinent for Catholics in other dioceses and even other countries.

“Dear sisters, dear brothers,

“Dear sisters, dear brothers,

Yes, it is true that image was often the first thing that needed protection, instead of the victims of an abusive priest, or so many in the Church thought and acted upon. And no, this is not really what Msgr. Anatrella, speaking at the regular course for new bishops in the Vatican (a previous meeting pictured), said.

Yes, it is true that image was often the first thing that needed protection, instead of the victims of an abusive priest, or so many in the Church thought and acted upon. And no, this is not really what Msgr. Anatrella, speaking at the regular course for new bishops in the Vatican (a previous meeting pictured), said. Wednesday is Ash Wednesday, the start of Lent (yes, it’s almost Lent already), and in this Holy Year of Mercy it is also the day of another notable event: the day on which more than one thousand special “missionaries of mercy” are sent out by the Pope into the world, to manifest God’s mercy in a specific way, by their ability to forgive the most grave of sins, which are usually beholden to bishops or the Pope alone.

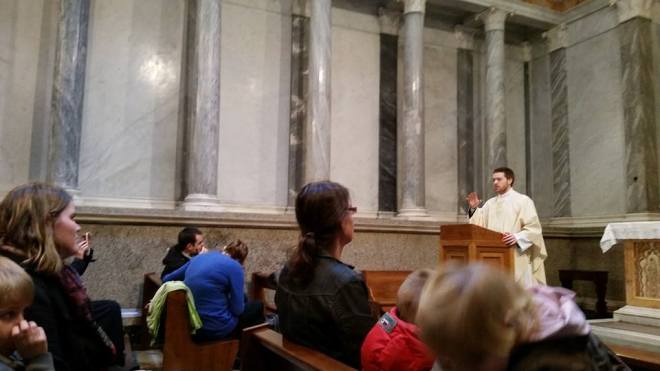

Wednesday is Ash Wednesday, the start of Lent (yes, it’s almost Lent already), and in this Holy Year of Mercy it is also the day of another notable event: the day on which more than one thousand special “missionaries of mercy” are sent out by the Pope into the world, to manifest God’s mercy in a specific way, by their ability to forgive the most grave of sins, which are usually beholden to bishops or the Pope alone. 13 priests from the Netherlands and 33 from Belgium (11 from Flanders, 22 from Wallonia) will be appointed as missionaries of mercy. One of the Dutch priests is Fr. Johannes van Voorst, of the Diocese of Haarlem-Amsterdam (one of seven from that diocese; the other six come from the Diocese of Roermond). Fr. Johannes (seen above offering Mass at St. Paul Outside the Walls today) will be going to Rome to receive his mandate, together with some 700 of his brother priests (the remaining 350 or so will receive their mandate at home). His adventures in Rome can be followed via

13 priests from the Netherlands and 33 from Belgium (11 from Flanders, 22 from Wallonia) will be appointed as missionaries of mercy. One of the Dutch priests is Fr. Johannes van Voorst, of the Diocese of Haarlem-Amsterdam (one of seven from that diocese; the other six come from the Diocese of Roermond). Fr. Johannes (seen above offering Mass at St. Paul Outside the Walls today) will be going to Rome to receive his mandate, together with some 700 of his brother priests (the remaining 350 or so will receive their mandate at home). His adventures in Rome can be followed via

“We have extensively discussed the concepts of mercy and truth, grace and justice, which are constantly treated as being in opposition to one another, and their theological relationships. In God they are certainly not in opposition: as God is love, justice and mercy come together in Him. The mercy of God is the fundamental truth of revelation, which is not opposed to other truths of revelation. It rather reveals to us the deepest reason, as it tells us why God empties Himself in His Son and why Jesus Christ remains present in His Church through His word and His sacraments. The mercy of God reveals to us in this way the reason and the entire purpose of the work of salvation. The justice of God is His mercy, with which He justifies us.

“We have extensively discussed the concepts of mercy and truth, grace and justice, which are constantly treated as being in opposition to one another, and their theological relationships. In God they are certainly not in opposition: as God is love, justice and mercy come together in Him. The mercy of God is the fundamental truth of revelation, which is not opposed to other truths of revelation. It rather reveals to us the deepest reason, as it tells us why God empties Himself in His Son and why Jesus Christ remains present in His Church through His word and His sacraments. The mercy of God reveals to us in this way the reason and the entire purpose of the work of salvation. The justice of God is His mercy, with which He justifies us. Today Archbishop André-Joseph Léonard marks his 75th birthday, and his letter of resignation will be delivered to the desk of Archbishop Giacinto Berloco, the Apostolic Nuncio to Belgium, who will forward it to Rome. All this is foreseen in canon law, but the immediate outcome has several options.

Today Archbishop André-Joseph Léonard marks his 75th birthday, and his letter of resignation will be delivered to the desk of Archbishop Giacinto Berloco, the Apostolic Nuncio to Belgium, who will forward it to Rome. All this is foreseen in canon law, but the immediate outcome has several options. About education, he later had to

About education, he later had to  After his retirement, and contrary to his previously expressed wish to leave Brussels, Archbishop Léonard will live with the

After his retirement, and contrary to his previously expressed wish to leave Brussels, Archbishop Léonard will live with the  The Holy Father may choose to elevate one of the suffragan bishops of Flanders. These are Bishop Jozef de Kesel of Bruges, Luc van Looy of Ghent, Johan Bonny of Antwerp and Patrick Hoogmartens of Hasselt. Bishop Léon Lemmens, auxiliary bishop for the Flemish part of Mechelen-Brussels, and Jean Kockerols, auxiliary for Brussels (pictured at right), may also be added to this group. At 73, Bishop van Looy is too close to his own retirement to be a likely choice. The others are between 56 and 67, so their age is no issue. Three bishops (De Kesel, Lemmens and Kockerols) know the archdiocese well, as they serve or have served as auxiliary bishops in it. There are also bishops who are no strangers to Rome or to the Pope personally. Bishop van Looy accompanied the young people of Verse Vis when they interviewed the Pope last year. Bishop Lemmens worked in Rome before being appointed as auxiliary bishop and Bishop Kockerols is internationally active as one of the vice-presidents of the Commission of the Bishops’ Conferences of the European Union (COMECE). Bishop Bonny had made headlines for himself in relation to the Synod of Bishops, so he will also not be unknown in Rome. The only relatively unknown bishop is Patrick Hoogmartens, but he, at least, has a motto that should appeal to the current papacy: “Non ut iudicet, sed ut salvetur” (Not to judge, but to save, John 3:17).

The Holy Father may choose to elevate one of the suffragan bishops of Flanders. These are Bishop Jozef de Kesel of Bruges, Luc van Looy of Ghent, Johan Bonny of Antwerp and Patrick Hoogmartens of Hasselt. Bishop Léon Lemmens, auxiliary bishop for the Flemish part of Mechelen-Brussels, and Jean Kockerols, auxiliary for Brussels (pictured at right), may also be added to this group. At 73, Bishop van Looy is too close to his own retirement to be a likely choice. The others are between 56 and 67, so their age is no issue. Three bishops (De Kesel, Lemmens and Kockerols) know the archdiocese well, as they serve or have served as auxiliary bishops in it. There are also bishops who are no strangers to Rome or to the Pope personally. Bishop van Looy accompanied the young people of Verse Vis when they interviewed the Pope last year. Bishop Lemmens worked in Rome before being appointed as auxiliary bishop and Bishop Kockerols is internationally active as one of the vice-presidents of the Commission of the Bishops’ Conferences of the European Union (COMECE). Bishop Bonny had made headlines for himself in relation to the Synod of Bishops, so he will also not be unknown in Rome. The only relatively unknown bishop is Patrick Hoogmartens, but he, at least, has a motto that should appeal to the current papacy: “Non ut iudicet, sed ut salvetur” (Not to judge, but to save, John 3:17). Archbishop Léonard’s coat of arms

Archbishop Léonard’s coat of arms